Jake Gyllenhaal plays his teenaged son, who winds up trapped in the New York Public Library with a small group of survivors after a tidal wave devastates the city. Father Dennis Quaid is a climatologist whose proclamations of doom fall on deaf ears. The Day After Tomorrow views the arrival of a new global ice age through the adventures of one all-American family. Admittedly, it does so in the most ludicrously sensationalist manner possible, but it still opened the door for a fruitful micro-genre of which we’ve already covered several notable examples. Directed by Roland Emmerich, The Day After Tomorrow was a major box office hit in 2004, and one of the first popcorn blockbusters to openly engage with the issue of climate change. We conclude our summer of disaster movies with a dubious modern classic. The scientific view of The Day After Tomorrow is still that it's absurd, but the latest science is also showing that the ideas and predictions underlying it were real, and they could soon make absurd-seeming weather extremes a little more commonplace.Listen to our The Day After Tomorrow episode on: And a colder northern Atlantic paradoxically brings warmer air to Europe: in fact, a record European heat wave in 2015 has been linked to record cold Atlantic waters.

Not likely, but a slowdown of the Gulf Stream System can make the consequences of sea-level rise for places like New York and Boston more dire. "We are only beginning to understand the consequences of this unprecedented process - but they might be disruptive."ĭoes this mean it's possible for North America to become essentially covered by glaciers in the span of a single weekend as Hollywood would have us believe?

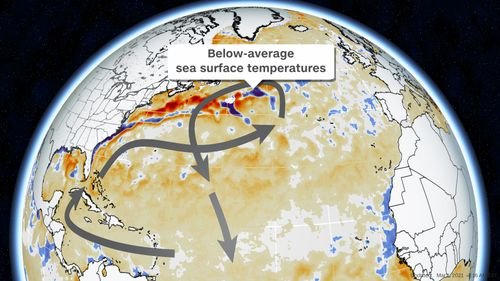

"If we do not rapidly stop global warming, we must expect a further long-term slowdown of the Atlantic overturning," explains Alexander Robinson of the University of Madrid, who co-authored the PIK study. The system is not on the brink of total collapse, as we see in The Day After Tomorrow, but the researchers do conclude that major ocean circulation has slowed down by about 15 percent since the middle of the 20th century. This helps preserve the weather patterns life is built around. The AMOC or Gulf Stream System is important as a key means of transporting heat around the globe, pushing warm water to the north and cold water to the south. Together, the two studies paint a picture of a weakened system that began to slow down around 150 years ago and really started to lose steam in recent decades as global temperatures rise. Delia Oppo, a senior scientist with WHOI and co-author of the study. "This weakening of the Atlantic's overturning began near the end of the Little Ice Age, a centuries-long cold period that lasted until about 1850," said Dr.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)